If you're looking for ------- head over to the next *********

If you want to talk about a “rise” of the novel, it’s possible that narrators grew up right along with them. Theirs was a stunted growth though, as we end up with narrators that know too much (cunning little Pamela Andrews must have been the original owner of the time-turner described in Harry Potter. How else would she have time to write so much?) and ones that know too little (the narrator in Love in Excess could tell you how her characters feel and react, but she’s sure you can imagine it for yourself).

It would only make sense, then, that Sterne would take advantage of this narrative crisis of identities and give us a “dark veil” of narratives, in which he is at once Sterne, the author, Shandy, the narrator, and sometimes he is even the omniscient, (now) powerful material text itself!

Tristram Shandy has a story to tell: that of his birth, unbirth, development, travels, of his uncle, his uncle’s mistress, of his father’s clock, of medical and rhetorical mishaps…well, he has many stories to tell. But unlike other narrators, this character has a double personality: he is both the Tristram Shandy who writes his memoirs and knows there’s a reader on the other side of the page keeping him alive, but he is simultaneously (and sometimes uncomfortably, for us) aware—and part of—Laurence Sterne, the real-life hand holding his and the real life author who will publish the story. Amongst the wondering tales that fill in the blanks, this is really a story of writing, the difficulty of words and the surprising power of non-decipherable objects like black and marbled pages, dashes and asterisks. This is a story about a fictional book that’s also a material, published book; of a novel that’s actually a narrative experiment; of an author that knows too much about the rules of printing and selling not to find it absurdly contrived. Harder than digging for linearity or coherence, this novel challenges our powers to be fictional and actual readers, and to thread together a brilliant project about the nature of composing, setting, binding and printing books—a (his)tory (see the clever move there?) that is an incredible “always already” in which the book is in production and already produced.

Specific references and their location in the text (note: I've recently discovered that there are editions that even divide the books differently, so you may still find it relatively impossible to locate these without a bit of careful reading):

READER: 88 references

EDIT/EDITING: 3 references.

PUBLISH: 15 references

WRITER: 24

WRITING: 44 references.

PRINT: 26ish. See below.

BOOKSELLER: 3 references

Some direct quotes, lifted from the author, with incredible insight.

—No doubt, Sir,—there is a whole chapter wanting here—and a chasm of ten pages made in the book by it—but the book-binder is neither a fool, or a knave, or a puppy—nor is the book a jot more imperfect (at least upon that score)—but, on the contrary, the book is more perfect and complete by wanting the chapter, than having it, as I shall demonstrate to your reverences in this manner.—I question first, by-the-bye, whether the same experiment might not be made as successfully upon sundry other chapters—but there is no end, an' please your reverences, in trying experiments upon chapters—we have had enough of it—So there's an end of that matter. (2.LX)

The following are all the instances of the words "write", "writer" and "writing", followed by references and commentary. You can download the tabled (and ruled) version under "downloads."

Quotations are in purple, organized by Volume and Chapter. Commentary follows in green.

______________________________*****************______________________________________________________________________________**********************__________________

I.ii à [the homunculus] is a Being of as much activity, ---- and, in all senses of the word, as much and as truly our fellow-creature as my Lord Chancellor of England. -- He may be benefited, he may be injured, -- he may obtain redress; -- in a word, he has all the claims and rights of humanity, which Tully, Puffendorff, or the best ethick writers allow to arise out of that state and relation.Sterne begins his narrative implying that even before he was a fetus he already had authorial, ethical and emotional claims to history. The next few chapters (cited, but not quoted) contain instances of other types from writers from whom Shandy attempts to differentiate himself. I.xxi à logical writers on the naming of rhetorical arguments

I.xxii à see reader reference “any writer in Great-Britain” (writing as a serious business).

I.xxii à see reader and digressions reference

I.iv à For which cause, right glad I am, that I have begun the history of myself in the way I have done ; and that I am able to go on tracing every thing in it, as Horace says, ab Ovo. Horace, I know, does not recommend this fashion altogether : But that gentleman is speaking only of an epic poem or a tragedy ; -- (I forget which) -- besides, if it was not so, I should beg Mr. Horace's pardon ; -- for in writing what I have set about, I shall confine myself neither to his rules, nor to any man's rules that ever lived. To such, however, as do not choose to go so far back into these things, I can give no better advice, than that they skip over the remaining part of this Chapter ; for I declare before hand, 'tis wrote only for the curious and inquisitive. ---------- Shut the door. -------- For someone that refuses to conform to norms, Tristram Shandy sure loves his classical references!

Indeed, his project is unique in its lack of order, and Tristram here invites his readers to be selective about the narrative, and not feel like they need to follow each loose strand of information—on the other hand, however, if you choose to do this, you’re obviously not “curious and inquisitive!” Sterne plays with his reader, creating and imaginary writer that is entitled to also imagine his readers. I.xv àsee reference to publishing.

I.xviii à it is no more than a week from this very day, in which I am now writing this book for the edification of the world, -- which is March 9, 1759, ----

One of Shandy’s many self-aware admittances of his genius. I.xxi à ---Pray what was the man's name, -- for I write in such a hurry, I have no time to recollect or look for it, ---- who first made the observation, ``That there was great inconstancy in our air and climate ? '' Whoever he was, 'twas a just and good observation in him. ---- But the corollary drawn from it, namely, ``That it is this which has furnished us with such a variety of odd and whimsical characters ;'' -- that was not his ; ---- it was found out by another man, at least a century and a half after him : -- Then again, -- that this copious store-house of original materials, is the true and natural cause that our Comedies are so much better than those of France, or any others that either have, or can be wrote upon the Continent ; ---- that discovery was not fully made till about the middle of king William's reign, -- when the great Dryden, in writing one of his long prefaces, (if I mistake not) most fortunately hit upon it. Indeed towards the latter end of queen Anne, the great Addison began topatronize the notion, and more fully explained it to the world in one or two of his Spectators ; -- but the discovery was not his. -- Then, fourthly and lastly, that this strange irregularity in our climate, producing so strange an irregularity in our characters, ---- doth thereby, in some sort, make us amends, by giving us somewhat to make us merry with when the weather will not suffer us to go out of doors, -- that observation is my own ; -- and was struck out by me this very rainy day, March 26, 1759, and betwixt the hours of nine and ten in the morning. ... gradually been creeping upwards towards that of their perfections,from which, if we may form a conjecture from the advances of these last seven years, we cannot possibly be far off. When that happens, it is to be hoped,it will put an end to all kind of writings whatsoever ; -- the want of all kind ofwriting will put an end to all kind of reading ; -- and that in time, As war begets poverty, poverty peace, ---- must, in course, put an end to all kind of knowledge, -- and then ---- we shall have all to begin over again ; or, in other words, be exactly where we started.This long passage discusses the theory that the weather can form a person’s character and thus that comedies can only come from warmer climates. However, Sterne/Shandy fears that these types of theorizing on the nature of writing impede creative production, and threatens to eliminate all sorts of writing and reading.

This is the first of many references to Shandy’s rushed and unedited mode of writing. In the past, this has led critics to suggest the we can conflate Sterne and Shady and call the book itself a chaotic, disorganized piece. However, much evidence has surfaced to prove the contrary, including many letters from Sterne himself and his efforts to choose even the paper and font type that was used for his book (see Yoklavich et. al). Mary de la Riviere Manley (amongst others) implies in her preface to The Secret History of Queen Zarah (1705) that the English aren’t made of the same stock as the French, because they are of a “much more brisk and impetuous Humour” and “naturally have no taste for long-winded Performances (33). Of course the irony is that books like Sterne’s play a cat and mouse game with the reader that dares them to stop reading, knowing full well that curiosity will get the best of them. Along with Richard Steele, Joseph Addison published a periodical called “The Spectator,” in which a main character (for which the periodical is named) commentated on various social and political affairs. “The Spectator” was immensely popular, and played a huge role in the "structural transformation of the public sphere” (Habermas). II.iv à I Would not give a groat for that man's knowledge in pen-craft, who does not understand this, ---- That the best plain narrative in the world, tack'd very close to the last spirited apostrophe to my uncle Toby, -- would have felt both cold and vapid upon the reader's palate ; -- therefore I forthwith put an end to the chapter, -- though I was in the middle of my story. ------ Writers of my stamp have one principle in common with painters. --Where an exact copying makes our pictures less striking, we choose the less evil ; deeming it even more pardonable to trespass against truth, than beauty. --

Shandy once again makes the reference that writing is like painting; the reader is once more teased with the invisible, untellable narrative: because Shandy feels that he can do the story no justice, he decides to just stop mid-way. Don’t hold your breath, dear reader, he means it. This story is now lost to your imagination.

Sterne is also mocking the drive for realism in novel writing: if one were to be absolutely realistic and stick to the facts, some stories would simply be boring. If his narrator is to be true to his realism but also insist on entertaining, he must sometimes disappoint by omission. II.xi à WRiting, when properly managed,(as you may be sure I think mine is) is but a different name for conversation : As no one, who knows what he is about in good company, would venture to talk all ; -- so no author, who understands the just boundaries of decorum and good breeding, would presume to think all : The truest respect which you can pay to the reader's understanding, is to halve this matter amicably, and leave him something to imagine, in his turn, as well as yourself.

This is one of Shandy’s famous quotes. However, as Roger Moss reminds us, “he doesn’t say this, he writes it, and the very parenthesis upon which both the ‘proof’ and the air of conversation rest is a visual effect of punctuation in the most aural way possible ... we are still admiring a virtuoso performance upon an instrument that is essentially unlike the thing it is imitating”(179). II.xxii à I like the sermon well, replied my father, ---- 'tis dramatic, ---- and there issomething in that way of writing, when skilfully managed, which catches the attention.

II.xxvii à Sir, quoth Dr. Slop, Trim is certainly in the right ; for the writer, (who I perceive is a Protestant) by the snappish manner in which he takes up the Apostle, is certainly going to abuse him, -- if this treatment of him has not done it already Trim and Dr. Slop discuss the possibility of guessing the author’s religion by the tone of the pamphlet. There is the implication here that a writer will betray his personal interests even in his style of writing. Anti-Catholic pamphlets abounded from the very start of the English Reformation. However, depending on the ruling monarch, some of these publications were dangerous to the authors and printers, and had to be done clandestinely.

II.xix à I Have dropp'd the curtain over this scene for a minute, -- to remind you of one thing, -- and to inform you of another. What I have to inform you, comes, I own, a little out of its due course ; -- for it should have been told a hundred and fifty pages ago, but that I foresaw then 'twould come in pat hereafter, and be of more advantage here than elsewhere. -- Writers had need look before them to keep up the spirit and connection of what they have in hand. When these two things are done, -- the curtain shall be drawn up again, and my uncle Toby, my father, and Dr. Slop shall go on with their discourse, without any more interruption.

Writing becomes both a faked performance and a literal editing exercise: on the one hand, the reader is facing a stage and the writer, as master of ceremonies, can draw and unveil the curtain when he pleases; on the other hand, it is the writer’s responsibility to be aware of when to properly introduce information.

This could be also a criticism towards serial novels, which often relied on the same set of characters but forgot to be true to their original outlines, or refused to remind the reader of what had happened in previous volumes (see Warner’s definition of “formula fiction,” Licensing Entertainment pp. 112—116). III.xx à (in the “preface”) Bless us ! -- what noble work we should make ! --- how should I tickle it off ! ---- and what spirits should I find myself in, to be writing away for such readers ! -- and you, -- just heaven ! ---- with what raptures would you sit and read Shandy writes himself into a frenzy imagining the type of collaborative work he and his reader can create. He has to stop and collect himself, only to move on to a completely different topic. III.xxà It must however be confessed on this head, that, as our air blows hot and cold, ---- wet and dry, ten times in a day, we have them in no regular and settled way ; ---- so that sometimes for near half a century together, there shall be very little wit or judgment, either to be seen or heard of amongst us : ---- the small channels of them shall seem quite dried up, -- then all of a sudden the sluices shall break out, and take a fit of running again like fury, -- you would think they would never stop : ---- and then it is, that in writing and fighting, and twenty other gallant things, we drive all the world before us.

III.xxxi à Now, before I venture to make use of the word Nose a second time, --- to avoid all confusion in what will be said upon it, in this interesting part of my story, it may not be amiss to explain my own meaning, and define, with all possible exactness and precision, what I would willingly be understood to mean by the term : being of opinion, that 'tis owing to the negligence and perverseness of writers, in despising this precaution, and to nothing else, ---- That all the polemical writings in divinity, are not as clear and demonstrative as those upon a Will o' the-Wisp, or any other sound part of philosophy, and natural pursuit ; in order to which, what have you to do, before you set out, unless you intend to go puzzling on to the day of judgment, Sterne responds to the critical fear of the seductive power of novels by coyly alluding –yet never referring to—sexual content. The recurring narrative of his nose promises to be a story about something else entirely, but immediately turns around and blames the reader for his/her lewd imaginations. III.xxxiv à There was one plaguy rub in the way of this, ---- the scarcity of materials to make any thing of a defence with, in case of a smart attack ; inasmuch as few men of great genius had exercised their parts in writing books upon the subject of great noses : by the trotting of my lean horse, the thing is incredible ! and I am quite lost in my understanding when I am considering what a treasure of precious time and talents together has been wasted upon worse subjects, ---- and how many millions of books in all languages, and in all possible types and bindings, have been fabricated upon points not half so much tending to the unity and peacemaking of the world.

In his “Conjectures on Original Composition” Young refers to the print market as an overgrown garden that needs pruning from weeds (imitators). Same à --- For in the account which Hafen Slawkenbergius gives the world of his motives and occasions for writing, and spending so many years of his life upon this one work -- towards the end of his prolegomena, which by the bye should have come first, ---- but the bookbinder has most injudiciously placed it betwixt the analitical contents of the book, and the book itself

This reference to the bookbinder’s mistake in placing a section of the book in the wrong place foreshadows to the blank page in Volume VI where Shandy will be careful to remove the blame from his bookbinder. Perhaps these two references, read together, can say something to Sterne’s great investment in the production of his books (see Moss, Curtis, Yoklavich, et. al for all the interventions Sterne has made in the publishing and typesetting).

III.xxxviii à And to do justice to Slawkenbergius, he has entered the list with a stronger lance, and taken a much larger career in it, than any one man who had ever entered it before him, ---- and indeed, in many respects, deserves to be en-nich'd as a prototype for all writers, of voluminous works at least, to model their books by, ---- for he has taken in, Sir, the whole subject, -- examined every part of it, dialectically, -- then brought it into full day ; dilucidating it with all the light which either the collision of his own natural parts could strike, --- or the profoundest knowledge of the sciences had impowered him to cast upon it, ---- collating, collecting and compiling, -- begging, borrowing, and stealing, as he went along, all that had been wrote or wrangled thereupon in the schools and porticos of the learned : so that Slawkenbergius his book may properly be considered, not only as a model, -- but as a thorough-stitch'd DIGEST and regular institute of noses ; comprehending in it, all that is, or can be needful to be known about them.

This seems to also connect to Shandy’s description of the impossible project of the Tristrapedia, and makes the reader question the realistic possibility of “collating, collecting and compiling, -- begging, borrowing, and stealing” everything that could be said about a given topic. IV.pre à I dip not my pen into my ink to excuse the surrender of yourselves -- 'tis to write your panegyrick. Shew me a city so macerated with expectation -- who neither eat, or drank, or slept, or prayed, or hearkened to the calls either of religion or nature for seven and twenty days together, who could have held out one day longer.

IV.vii à So stood my father, holding fast his fore-finger betwixt his finger and his thumb, and reasoning with my uncle Toby as he sat in his old fringed chair, valanced around with party-coloured worsted bobs -- O Garrick ! what a rich scene of this would thy exquisite powers make ! and how gladly would I write such another to avail myself of thy immortality, and secure my own behind it.

IV.ix à - What a lucky chapter of chances has this turned out ! for it has saved me the trouble of writing one express, and in truth I have anew already upon my hands without it ---- Have not I promised the world a chapter of knots ? two chapters upon the right and the wrong end of a woman ? a chapter upon whiskers ? a chapter upon wishes ? -- a chapter of noses ? -- No, I have done that -- a chapter upon my uncle Toby's modesty ? to say nothing of a chapter upon chapters, which I will finish before I sleep -- by my great grandfather's whiskers, I shall never get half of 'em through this year.

Shandy enumerates all the different subjects he has promised to write about, once again playing with the dangerous (or exciting) looming of infinite possibilities.

IV.x à Now this, you must know, being my chapter upon chapters, which I promised to write before I went to sleep, I thought it meet to ease my conscience entirely before I lay'd down, by telling the world all I knew about the matter at once : Is not this ten times better than to set out dogmatically with a sententious parade of wisdom, and telling the world a story of a roasted horse -- that chapters relieve the mind -- that they assist -- or impose upon the imagination -- and that in a work of this dramatic cast they are as necessary as the shifting of scenes -- with fifty other cold conceits, enough to extinguish the fire which roasted him. -- O ! but to understand this, which is a puff at the fire of Diana's temple-- you must read Lon-ginus -- read away -- if you are not a jot the wiser by reading him the first time over -- never fear -- read him again -- Avicenna and Licetus, read Aristotle's metaphysicks forty times through a piece, and never understood a single word. -- But mark the consequence -- Avicenna turned out a desperate writer at all kinds of writing -- for he wrote books de omni scribili ; and for Licetus (Fortunio) though all the world knows he was born a foetus *, of no more than five inches and a half in length, yet he grew to that astonishing height in literature, as to write a book with a title as long as himself ---- the learned know I mean his Gonopsychan-thropologia, upon the origin of the human soul. The chapter on chapters ends up being another pondering on the nature of time and length, and it explains the necessity of breaks and pauses in a text. However, chapters do not necessarily (as they certainly don’t here!) imply beginnings or ends—much like reading a book from cover to cover does not imply the book won’t be read again, and that select chapters won’t be excerpted for more careful reading.

IV.xiii à Was every day of my life to be as busy a day as this, -- and to take up, -- truce -- I will not finish that sentence till I have made an observation upon the strange state of affairs between the reader and myself, just as things stand at present -- an observation never applicable before to any one biographical writer since the creation of the world, but to myself -- and I believe will never hold good to any other, until its final destruction ---- and therefore, for the very novelty of it alone, it must be worth your worships attending to. I am this month one whole year older than I was this time twelve-month ; and having got, as you perceive, almost into the middle of my fourth volume -- and no farther than to my first day's life -- 'tis demonstrative that I have three hundred and sixty-four days more life to write just now, than when I first set out ; so that instead of advancing, as a common writer, in my work with what Ihave been doing at it -- on the contrary, I am just thrown so many volumes back -- was every day of my life to be as busy a day as this -- And why not ? -- and the transactions and opinions of it to take up as much description -- And for what reason should they be cut short ? as at this rate I should just live 364 times faster than I should write -- It must follow, an' please your worships, that the more I write, the more I shall have to write -- and consequently, the more your worships read, the more your worships will have to read. We get yet another reference to time, and the impossibility of making one’s writing mimic the literal passing of time. Though we are four volumes in, Tristram is only just been born, and at this rate the narrative will never end. Same è As for the proposal of twelve volumes a year, or a volume a month, it no way alters my prospect -- write as I will, and rush as I may into the middle of things, as Horace advises, -- I shall never overtake myself -- whipp'd and driven to the last pinch, at the worst I shall have one day the start of my pen -- and one day is enough for two volumes – and two volumes will be enough for one year. –

IV.xv àI Wish I could write a chapter upon sleep. A fitter occasion could never have presented itself, than what this moment offers, when all the curtains of the family are drawn -- the candles put out -- and no creature's eyes are open but a single one, for the other has been shut these twenty years, of my mother's nurse. It is a fine subject! And yet, as fine as it is, I would undertake to write a dozen chapters upon button-holes, both quicker and with more fame than a single chapter upon this.

IV.xvii à The different weight, dear Sir, -- nay even the different package of two vexations of the same weight, -- makes a very wide difference in our manners of bearing and getting through with them. -- It is not half an hour ago, when (in the great hurry and precipitation of a poor devil's writing for daily bread) I threw a fair sheet, which I had just finished, and carefully wrote out, slap into the fire, instead of the foul one.

IV.xxv. à But the painting of this journey, upon reviewing it, appears to be so much above the stile and manner of any thing else I have been able to paint in this book, that it could not have remained in it, without depreciating every other scene ; and destroying at the same time that necessary equipoise and balance, (whether of good or bad) betwixt chapter and chapter, from whence the just proportions and harmony of the whole work results. For my own part, I am but just set up in the business, so know little about it -- but, in my opinion, to write a book is for all the world like humming a song -- be but in tune with yourself, madam, 'tis no matter how high or how low you take it. – Shandy makes another reference to chapters that, for being too good, risk overshadowing the entire work and must thus be edited out. IV.xxvi à As Yorick pronounced the word point blank, my uncle Toby rose up to say something upon projectiles ---- when a single word, and no more, uttered from the opposite side of the table, drew every one's ears towards it -- a word of all others in the dictionary the last in that place to be expected -- a word I am ashamed to write -- yet must be written -- must be read ; -- illegal -- uncanonical -- guess ten thousand guesses, multiplied into themselves -- rack -- torture your invention for ever, you're where you was -- In short, I'll tell it in the next chapter.

One of Sterne’s many playful exchanges with the reader, in which we are teased with the promise of the worst of words and are only later reminded that our imagination is always a better substitution to a literal description on the page.

V.xvi à In about three years, or something more, my father had got advanced almost into the middle of his work. – Like all other writers, he met with disappointments. -- He imagined he should be able to bring whatever he had to say,into so small a compass, that when it was finished and bound, it might be rolled up in my mother's hussive. -- Matter grows under our hands. -- Let no man say, -- “Come -- I'll write a duodecimo.” Shandy refers to his father’s inability to complete his Tristrapedia and immediately reminds the reader of the meanderings of his own narrative. The fact that “matter grows under our hands” will be a recurring theme in the book. V.xx à My uncle Toby had just then been giving Yorick an account of the Battle of Steenkirk, and of the strange conduct of count Solmes in ordering the foot to halt, and the horse to march where it could not act; which was directly contrary to the king's commands, and proved the loss of the day. There are incidents in some families so pat to the purpose of what is going to follow, -- they are scarce exceeded by the invention of a dramatic writer ; -- I mean of ancient days. ----

The time for reverencing the Classics was over—in the 18th century, “novel” was the buzz word—writers wanted innovation, originality and the mark of true genius. This, according to Warner, was a response to the growing print culture and the necessity to respond to “the press’ thirst for new material” (134).

V.xxvi à First, Had the matter been taken into consideration, before the event happened, my father certainly would have nailed up the sash-window for good an' all ; --which, considering with what difficulty he composed books, -- he might have done with ten times less trouble, than he could have wrote the chapter : this argument I foresee holds good against his writing the chapter, even after the event; but 'tis obviated under the second reason, which I have the honour to offer to the world in support of my opinion, that my father did not write the chapter upon sash-windows and chamber-pots, at the time supposed, -- and it is this. ---- That, in order to render the Tristrapædia complete, -- I wrote the chapter myself.

The narrative of the sash-window incident intertwines all the different stories being told: it interpolates the actual book’s telling of it with Walter’s proposed (fiction) chapter on the Tristrapedia, which Tristram’s decision to write the chapter himself, both as part of his opinions and as a last addition to his father’s work. VI.xvii àIn all nice and ticklish discussions, -- (of which, heaven knows, there are but too many in my book) -- where I find I cannot take a step without the danger of having either their worships or their reverences upon my back -- I write one half full, -- and t'other fasting ; -- or write it all full, -- and correct it fasting; -- or write it fasting, -- and correct it full, for they all come to the same thing : -- So that with a less variation from my father's plan, than my father's from the Gothick -- I feel myself upon a par with him in his first bed of justice, -- and no way inferior to him in his second. -- These different and almost irreconcileable effects, flow uniformly from the wise and wonderful mechanism of nature, -- of which, -- be her's the honour. -- All that we can do, is to turn and work the machine to the improvement and better manufactury of the arts and sciences. Now, when I write full, -- I write as if I was never to write fasting again as long as I live ; -- that is, I write free from the cares, as well as the terrors of the world. -- I count not the number of my scars, -- nor does my fancy go forth into dark entries and bye corners to antedate my stabs. -- In a word, my pen takes its course ; and I write on as much from the fullness of my heart, as my stomach. -- But when, an' please your honours, I indite fasting, 'tis a different history. -- I pay the world all possible attention and respect, -- and have as great a share (whilst it lasts) of that understrapping virtue of discretion, as the best of you. -- So that betwixt both, I write a careless kind of a civil, nonsensical, good humoured Shandean book, which will do all your hearts good -- -- And all your heads too, -- provided you understand it.

Shandy himself decides upon a definition of “Shandean” style.

VI.xxi à -- for my uncle Toby took the liberty of incroaching upon his kitchen garden, for the sake of enlarging his works on the bowling green, and for that reason generally ran his first and second parallels betwixt two rows of his cabbages and his collyflowers ; the conveniences and inconveniences of which will be considered at large in the history of my uncle Toby's and the corporal's campaigns, of which, this I'm now writing is but a sketch, and will be finished, if I conjecture right, in three pages (but there is no guessing) -- The campaigns themselves will take up as many books ; and therefore I apprehend it would be hanging too great a weight of one kind of matter in so flimsy a performance as this, to rhapsodize them, as I once intended, into the body of the work -- surely they had better be printed apart, -- we'll consider the affair -- so take the following sketch of them in the mean time.

This is one of many passages in which Tristram reminds us that he is writing extemporaneously, and that we are, as readers, not only privy of the finished, printed work, but somehow also privy to the planning and process of preparing the book for the press. Time is compressed, and we are left expectant of a finished volume that is already finished.

VI. xxxvi àNOW, because I have once or twice said, in my inconsiderate way of talking, That I was confident the following memoirs of my uncle Toby's courtship of widow Wadman, whenever I got time to write them, would turn out one of the most compleat systems, both of the elementary and practical part of love and love-making, that ever was addressed to the world -- are you to imagine from thence, that I shall set out with a description of what love is?

Early writers like Haywood and Behn capitalized on the many ways to describe and understand love, and presented readers with a myriad of points-of-view with which to understand their characters’ motivations. VI.xl à Pray can you tell me, -- that is, without anger, before I write my chapter upon straight lines -- by what mistake -- who told them so -- or how it has come to pass, that your men of wit and genius have all along confounded this line, with the line of GRAVITATION.

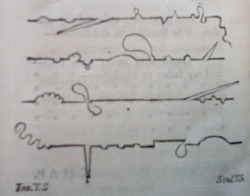

VI.xl à (straight lines) If I mend at this rate, it is not impossible -- by the good leave of his grace of Benevento's devils -- but I may arrive hereafter at the excellency of going on even thus ;which is a line drawn as straight as I could draw it, by a writing-master's ruler, (borrowed for that purpose) turning neither to the right hand or to the left. This right line, -- the path-way for Christians to walk in ! say divines -- -- The emblem of moral rectitude ! says Cicero -- -- The best line ! say cabbage-planters -- is the shortest line, says Archimedes, which can be drawn from one given point to another. --

Linear narrative becomes a literal, physical line that can be drawn on paper with a ruler.

See image on Tristrapedia webpage, under “Stolen.”

VII.i à NO -- I think, I said, I would write two volumes every year, provided the vile cough which then tormented me, and which to this hour I dread worse than the devil, would but give me leave -- and in another place -- (but where, I can't recollect now) speaking of my book as a machine, and laying my pen and ruler down cross-wise upon the table, in order to gain the greater credit to it -- I swore it should be kept a going at that rate these forty years if it pleased but the fountain of life to bless me so long with health and good spirits.

Writing as synonymous for staying alive is another recurring theme in the book.

VII.iv à NOW before I quit Calais,'' a travel-writer would say, “it would not be amiss to give some account of it”' -- Now I think it very much amiss -- that a man cannot go quietly through a town, and let it alone, when it does not meddle with him, but that he must be turning about and drawing his pen at every kennel he crosses over, merely, o' my conscience, for the sake of drawing it ; because, if we may judge from what has been wrote of these things, by all who have wrote and gallop'd -- or who have gallop'd and wrote, which is a different way still ; or who for more expedition than the rest, have wrote-galloping, which is the way I do at present -- from the great Addison who did it with his satchel of school-books hanging at his a-- and galling his beast's crupper at every stroke -- there is not a galloper of us all who might not have gone on ambling quietly in his own ground (in case he had any) and have wrote all he had to write, dry shod, as well as not. For my own part, as heaven is my judge, and to which I shall ever make my last appeal -- I know no more of Calais … I would lay any travelling odds, that I this moment write a chapter upon Calais as long as my arm ; and with so distinct and satisfactory a detail of every item, which is worth a stranger's curiosity in the town -- that youwould take me for the town clerk of Calais itself -- and where, sir, would be the wonder? was not Democritus, wholaughed ten times more than I -- townclerk of Abdera? and was not (I forget his name) who had more discretion than us both, town-clerk of Ephesus? -- it should be penn'd moreover, Sir, with so much knowledge and good sense, and truth, and precision -- -- Nay -- if you don't believe me, you may read the chapter for your pains.

VII.xxvi à -- Alas! Madam,had it been upon some melancholy lecture of the cross -- the peace of meekness, or the contentment of resignation -- I had not been incommoded : or had I thought of writing it upon the purer abstractions of the soul, and that food of wisdom, and holiness, and contemplation, upon which the spirit of man (when separated from the body) is to subsist for ever -- You would have come with a better appetite from it -- -- I wish I never had wrote it : but as I never blot any thing out -- let us use some honest means to get it out of our heads directly.

Yet another reference to the (supposedly) unedited nature of the work.

VII.xxviii à --NOW this is the most puzzled skein of all -- for in this last chapter, as far at least as it has help'd me through Auxerre, I have been getting forwards in two different journies together, and with the same dash of the pen -- for I have got entirely out of Auxerre in this journey which I am writing now, and I am got half way out of Auxerre in that which I shall write hereafter -- There is but a certain degree of perfection in every thing ; and by pushing at something beyond that, I have brought myself into such a situation, as no traveller ever stood before me ; for I am this moment walking across the market-place of Auxerre with my father and my uncle Toby, in our way back to dinner -- and I am this moment also entering Lyons with my postchaise broke into a thousand pieces -- and I am moreover this moment in a handsome pavillion built by Pringello*, upon the banks of the Garonne, which Mons. Sligniac has lent me, and where I now sit rhapsodizing all these affairs. -- Let me collect myself, and pursue my journey. In yet another play on time and realism, Shandy finds himself at once in Auxerre (at the point in the narrative) and out of it (presumably in “real time” leaving it). He is now beyond time itself, through the magic of writing! This is also a reminder of time running ahead of him, so he must keep writing if he hopes to catch up (which, arguably, he doesn’t want to happen).

VII.xlii à There is nothing more pleasing to a traveller -- or more terrible to travelwriters, than a large rich plain ; especially if it is without great rivers or bridges ; and presents nothing to the eye, but one unvaried picture of plenty : for after they have once told you that 'tis delicious! or delightful! (as the case happens) -- that the soil was grateful, and that nature pours out all her abundance, &c. . . . they have then a large plain upon their hands, which they know not what to do with -- and which is of little or no use to them but to carry them to some town ; and that town, perhaps of little more, but a new place to start from to the next plain -- and so on. -- This is most terrible work ; judge if I don't manage my plains better.

Anachronistic reference: in Northanger Abbey, Catherine reflects her lack of knowledge about paining precisely because she finds Bath an utterly disinteresting landscape. Sterne plays with the fact that traditional landscapes in books tend to be rich and varied, and that there is more challenge in describing the mundane than in creating wonder. VIII.i àBut in this clear climate of fantasy and perspiration, where every idea, sensible and insensible, gets vent -- in this land, my dear Eugenius -- in this fertile land of chivalry and romance, where I now sit, unscrewing my ink-horn to write my uncle Toby's amours, and with all the meanders of JULIA's track in quest of her DIEGO in full view of my study window -- if thou comest not and takest me by the hand-- What a work is it likely to turn out! Let us begin it. Sterne once again titillates his reader while also taking the opportunity to mock novels that pretend to moralize readers while suggesting illicit moments “behind the curtains.” Here, however, Shandy calls his reader to join him, quite literally, by taking his hand and writing/walking along towards the sexual climax (pun intended...)

VIII.ii à The thing is this. That of all the several ways of beginning a book which are now in practice throughout the known world I am confident my own way of doing it is the best -- I'm sure it is the most religious -- for I begin with writing the first sentence -- and trusting to Almighty God for the second. 'Twould cure an author for ever of the fuss and folly of opening his streetdoor, and calling in his neighbours and friends, and kinsfolk, with the devil and all his imps, with their hammers and engines, &c. only to observe how one sentence of mine follows another, and how the plan follows the whole. Sterne blatantly challenges his readers (and critics) to find sense and linearity in his work (or any work for that matter). If it all comes down to the logic of sentences, any writer could argue that one sentence literally follows another! Again, the materiality of books is key: because books, words and pages are produced in a linear fashion, it is possible to argue that even this work is done in a clear, natural order of events, because each page follows another, each line follows its previous and thus the plan follows the whole. VIII.vi à I declare, I do not recollect any one opinion or passage of my life, where my understanding was more at a loss to make ends meet, and torture the chapter I had been writing, to the service of the chapter following it, than in the present case : one would think I took a pleasure in runing into difficulties of this kind, merely to make fresh experiments of getting out of `em -- Inconsiderate soul that thou art! What! are not the unavoidable distresses with which, as an author and a man, thou art hemm'd in on every side of thee -- are they,Tristram, not sufficient, but thou must entangle thyself still more? Is it not enough that thou art in debt, and that thou hast ten cart-loads of thy fifth and sixth volumes still -- still unsold, and art almost at thy wit's ends, how to get them off thy hands.

VIII.xvii à THESE attacks of Mrs. Wadman, you will readily conceive to be of different kinds ; varying from each other, like the attacks which history is full of, and from the same reasons. A general looker on, would scarce allow them to be attacks at all -- or if he did, would confound them all together -- but I write not to them : it will be time enough to be a little more exact in my descriptions of them, as I come up to them, which will not be for some chapters ;

IX.xii à-- Certainly, if there is any dependence upon Logic, and that I am not blinded by self-love, there must be something of true genius about me, merely upon this symptom of it, that I do not know what envy is : for never do I hit upon any invention or device which tendeth to the furtherance of good writing, but I instantly make it public ; willing that all mankind should write as well as myself. -- Which they certainly will, when they think as little.

Shandy’s self-aware understanding of his true genius reflects Young’s expectations that “genius ... is like a dear friend in our company under disguise; who, while we are lamenting his absence, drops his mask ... a poet of a strong imagination, and stronger vanity, on feeling it, might naturally enough realize the world’s mere compliment, and think himself truly inspired” (23). Here, of course, Shandy is a little misguided in considering himself a “genius”—though he may be accurately reflecting the flaws in Young’s vague and self-loving definitions. IX.xiii àNOW in ordinary cases, that is, when I am only stupid, and the thoughts rise heavily and pass gummous through my pen -- Or that I am got, I know not how, into a cold unmetaphorical vein of infamous writing, and cannot take a plumblift out of it for my soul ; so must be obliged to go on writing like a Dutch commentator to the end of the chapter, unless something be done -- -- I never stand conferring with pen and ink one moment ; for if a pinch of snuff or a stride or two across the room will not do the business for me --

IX.xivà AS I ever had any intention of beginning the Digression, I am making all this preparation for, till I come to the 15th chapter -- I have this chapter to put to whatever use I think proper -- I have twenty this moment ready for it -- I could write my chapter of Button-holes in it -- Or my chapter of Pishes, which should follow them -- Or my chapter of Knots, in case their reverences have done with them -- they might lead me into mischief : the safest way is to follow the tract of the learned, and raise objections against what I have been writing, tho'I declare beforehand, I know no more than my heels how to answer them. And first, it may be said, there is a pelting kind of thersitical satire, as black as the very ink 'tis wrote with -- (and by the bye, whoever says so is indebted to the muster-master general of the Grecian army, for suffering the name of so ugly and foul-mouth'd a man as Thersites to continue upon his roll -- for it has furnished him with an epithet) -- in these productions, he will urge, all the personal washings and scrubbings upon earth do a sinking genius no sort of good -- but just the contrary, inasmuch as the dirtier the fellow is, the better generally he succeeds in it.

IX.xv àTo this, I have no other answer -- at least ready -- but that the Archbishop of Benevento wrote his nasty Romance of the Galatea, as all the world knows, in a purple coat, waistcoat, and purple pair of breeches ; and that the penance set him of writing a commentary upon the book of the Revelations, as severe as it was look'd upon by one part of the world, was far from being deemed so, by the other, upon the single account of that Investment. Another objection to all this remedy, is its want of universality ; forasmuch as the shaving part of it, upon which so much stress is laid, by an unalterable law of nature excludes one half of the species entirely from its use : all I can say is, that female writers, whether of England, or of France, must e'en go without it -- As for the Spanish ladies -- I am in no sort of distress --

IX.xxv àWHEN we have got to the end of this chapter (but not before) we must all turn back to the two blank chapters, on the account of which my honour has lain bleeding this half hour -- I stop it, by pulling off one of my yellow slippers and throwing it with all my violence to the opposite side of my room, with a declaration at the heel of it -- -- That whatever resemblance it may bear to half the chapters which are written in the world, or, for aught I know, may be now writing in it -- that it was as casual as the foam of Zeuxis his horse : besides, I look upon a chapter which has only nothing in it with respect ; and considering what worse things there are in the world -- That it is no way a proper subject for satire -- -- Why then was it left so? And here, without staying for my reply, shall I be called as many blockheads, numskulls, doddypoles, dunderheads, ninny-hammers, goosecaps, joltheads, nincom-poops, and sh--t-a-beds -- and other unsavory appellations, as ever the cakebakers of Lerné, cast in the teeth of King Gargantua's shepherds -- And I'll let them do it, as Bridget said, as much as they please ; for how was it possible they should foresee the necessity I was under of writing the 25th chapter of my book before the 18th, &c. -- So I don't take it amiss -- All I wish is that it may be a lesson to the world, `` to let people tell their stories `` their own way.''

Shandy himself reminds the reader of the blank pages left behind in volume VI and forces a retracing of his steps.

The following are all the instances of the words "write", "writer" and "writing", followed by references and commentary. You can download the tabled (and ruled) version under "downloads."

Quotations are in purple, organized by Volume and Chapter. Commentary follows in green.

______________________________*****************______________________________________________________________________________**********************__________________

I.xxii à see reader reference “any writer in Great-Britain” (writing as a serious business).

I.xxii à see reader and digressions reference

I.iv à For which cause, right glad I am, that I have begun the history of myself in the way I have done ; and that I am able to go on tracing every thing in it, as Horace says, ab Ovo. Horace, I know, does not recommend this fashion altogether : But that gentleman is speaking only of an epic poem or a tragedy ; -- (I forget which) -- besides, if it was not so, I should beg Mr. Horace's pardon ; -- for in writing what I have set about, I shall confine myself neither to his rules, nor to any man's rules that ever lived. To such, however, as do not choose to go so far back into these things, I can give no better advice, than that they skip over the remaining part of this Chapter ; for I declare before hand, 'tis wrote only for the curious and inquisitive. ---------- Shut the door. -------- For someone that refuses to conform to norms, Tristram Shandy sure loves his classical references!

Indeed, his project is unique in its lack of order, and Tristram here invites his readers to be selective about the narrative, and not feel like they need to follow each loose strand of information—on the other hand, however, if you choose to do this, you’re obviously not “curious and inquisitive!” Sterne plays with his reader, creating and imaginary writer that is entitled to also imagine his readers. I.xv àsee reference to publishing.

I.xviii à it is no more than a week from this very day, in which I am now writing this book for the edification of the world, -- which is March 9, 1759, ----

One of Shandy’s many self-aware admittances of his genius. I.xxi à ---Pray what was the man's name, -- for I write in such a hurry, I have no time to recollect or look for it, ---- who first made the observation, ``That there was great inconstancy in our air and climate ? '' Whoever he was, 'twas a just and good observation in him. ---- But the corollary drawn from it, namely, ``That it is this which has furnished us with such a variety of odd and whimsical characters ;'' -- that was not his ; ---- it was found out by another man, at least a century and a half after him : -- Then again, -- that this copious store-house of original materials, is the true and natural cause that our Comedies are so much better than those of France, or any others that either have, or can be wrote upon the Continent ; ---- that discovery was not fully made till about the middle of king William's reign, -- when the great Dryden, in writing one of his long prefaces, (if I mistake not) most fortunately hit upon it. Indeed towards the latter end of queen Anne, the great Addison began topatronize the notion, and more fully explained it to the world in one or two of his Spectators ; -- but the discovery was not his. -- Then, fourthly and lastly, that this strange irregularity in our climate, producing so strange an irregularity in our characters, ---- doth thereby, in some sort, make us amends, by giving us somewhat to make us merry with when the weather will not suffer us to go out of doors, -- that observation is my own ; -- and was struck out by me this very rainy day, March 26, 1759, and betwixt the hours of nine and ten in the morning. ... gradually been creeping upwards towards that of their perfections,from which, if we may form a conjecture from the advances of these last seven years, we cannot possibly be far off. When that happens, it is to be hoped,it will put an end to all kind of writings whatsoever ; -- the want of all kind ofwriting will put an end to all kind of reading ; -- and that in time, As war begets poverty, poverty peace, ---- must, in course, put an end to all kind of knowledge, -- and then ---- we shall have all to begin over again ; or, in other words, be exactly where we started.This long passage discusses the theory that the weather can form a person’s character and thus that comedies can only come from warmer climates. However, Sterne/Shandy fears that these types of theorizing on the nature of writing impede creative production, and threatens to eliminate all sorts of writing and reading.

This is the first of many references to Shandy’s rushed and unedited mode of writing. In the past, this has led critics to suggest the we can conflate Sterne and Shady and call the book itself a chaotic, disorganized piece. However, much evidence has surfaced to prove the contrary, including many letters from Sterne himself and his efforts to choose even the paper and font type that was used for his book (see Yoklavich et. al). Mary de la Riviere Manley (amongst others) implies in her preface to The Secret History of Queen Zarah (1705) that the English aren’t made of the same stock as the French, because they are of a “much more brisk and impetuous Humour” and “naturally have no taste for long-winded Performances (33). Of course the irony is that books like Sterne’s play a cat and mouse game with the reader that dares them to stop reading, knowing full well that curiosity will get the best of them. Along with Richard Steele, Joseph Addison published a periodical called “The Spectator,” in which a main character (for which the periodical is named) commentated on various social and political affairs. “The Spectator” was immensely popular, and played a huge role in the "structural transformation of the public sphere” (Habermas). II.iv à I Would not give a groat for that man's knowledge in pen-craft, who does not understand this, ---- That the best plain narrative in the world, tack'd very close to the last spirited apostrophe to my uncle Toby, -- would have felt both cold and vapid upon the reader's palate ; -- therefore I forthwith put an end to the chapter, -- though I was in the middle of my story. ------ Writers of my stamp have one principle in common with painters. --Where an exact copying makes our pictures less striking, we choose the less evil ; deeming it even more pardonable to trespass against truth, than beauty. --

Shandy once again makes the reference that writing is like painting; the reader is once more teased with the invisible, untellable narrative: because Shandy feels that he can do the story no justice, he decides to just stop mid-way. Don’t hold your breath, dear reader, he means it. This story is now lost to your imagination.

Sterne is also mocking the drive for realism in novel writing: if one were to be absolutely realistic and stick to the facts, some stories would simply be boring. If his narrator is to be true to his realism but also insist on entertaining, he must sometimes disappoint by omission. II.xi à WRiting, when properly managed,(as you may be sure I think mine is) is but a different name for conversation : As no one, who knows what he is about in good company, would venture to talk all ; -- so no author, who understands the just boundaries of decorum and good breeding, would presume to think all : The truest respect which you can pay to the reader's understanding, is to halve this matter amicably, and leave him something to imagine, in his turn, as well as yourself.

This is one of Shandy’s famous quotes. However, as Roger Moss reminds us, “he doesn’t say this, he writes it, and the very parenthesis upon which both the ‘proof’ and the air of conversation rest is a visual effect of punctuation in the most aural way possible ... we are still admiring a virtuoso performance upon an instrument that is essentially unlike the thing it is imitating”(179). II.xxii à I like the sermon well, replied my father, ---- 'tis dramatic, ---- and there issomething in that way of writing, when skilfully managed, which catches the attention.

II.xxvii à Sir, quoth Dr. Slop, Trim is certainly in the right ; for the writer, (who I perceive is a Protestant) by the snappish manner in which he takes up the Apostle, is certainly going to abuse him, -- if this treatment of him has not done it already Trim and Dr. Slop discuss the possibility of guessing the author’s religion by the tone of the pamphlet. There is the implication here that a writer will betray his personal interests even in his style of writing. Anti-Catholic pamphlets abounded from the very start of the English Reformation. However, depending on the ruling monarch, some of these publications were dangerous to the authors and printers, and had to be done clandestinely.

II.xix à I Have dropp'd the curtain over this scene for a minute, -- to remind you of one thing, -- and to inform you of another. What I have to inform you, comes, I own, a little out of its due course ; -- for it should have been told a hundred and fifty pages ago, but that I foresaw then 'twould come in pat hereafter, and be of more advantage here than elsewhere. -- Writers had need look before them to keep up the spirit and connection of what they have in hand. When these two things are done, -- the curtain shall be drawn up again, and my uncle Toby, my father, and Dr. Slop shall go on with their discourse, without any more interruption.

Writing becomes both a faked performance and a literal editing exercise: on the one hand, the reader is facing a stage and the writer, as master of ceremonies, can draw and unveil the curtain when he pleases; on the other hand, it is the writer’s responsibility to be aware of when to properly introduce information.

This could be also a criticism towards serial novels, which often relied on the same set of characters but forgot to be true to their original outlines, or refused to remind the reader of what had happened in previous volumes (see Warner’s definition of “formula fiction,” Licensing Entertainment pp. 112—116). III.xx à (in the “preface”) Bless us ! -- what noble work we should make ! --- how should I tickle it off ! ---- and what spirits should I find myself in, to be writing away for such readers ! -- and you, -- just heaven ! ---- with what raptures would you sit and read Shandy writes himself into a frenzy imagining the type of collaborative work he and his reader can create. He has to stop and collect himself, only to move on to a completely different topic. III.xxà It must however be confessed on this head, that, as our air blows hot and cold, ---- wet and dry, ten times in a day, we have them in no regular and settled way ; ---- so that sometimes for near half a century together, there shall be very little wit or judgment, either to be seen or heard of amongst us : ---- the small channels of them shall seem quite dried up, -- then all of a sudden the sluices shall break out, and take a fit of running again like fury, -- you would think they would never stop : ---- and then it is, that in writing and fighting, and twenty other gallant things, we drive all the world before us.

III.xxxi à Now, before I venture to make use of the word Nose a second time, --- to avoid all confusion in what will be said upon it, in this interesting part of my story, it may not be amiss to explain my own meaning, and define, with all possible exactness and precision, what I would willingly be understood to mean by the term : being of opinion, that 'tis owing to the negligence and perverseness of writers, in despising this precaution, and to nothing else, ---- That all the polemical writings in divinity, are not as clear and demonstrative as those upon a Will o' the-Wisp, or any other sound part of philosophy, and natural pursuit ; in order to which, what have you to do, before you set out, unless you intend to go puzzling on to the day of judgment, Sterne responds to the critical fear of the seductive power of novels by coyly alluding –yet never referring to—sexual content. The recurring narrative of his nose promises to be a story about something else entirely, but immediately turns around and blames the reader for his/her lewd imaginations. III.xxxiv à There was one plaguy rub in the way of this, ---- the scarcity of materials to make any thing of a defence with, in case of a smart attack ; inasmuch as few men of great genius had exercised their parts in writing books upon the subject of great noses : by the trotting of my lean horse, the thing is incredible ! and I am quite lost in my understanding when I am considering what a treasure of precious time and talents together has been wasted upon worse subjects, ---- and how many millions of books in all languages, and in all possible types and bindings, have been fabricated upon points not half so much tending to the unity and peacemaking of the world.

In his “Conjectures on Original Composition” Young refers to the print market as an overgrown garden that needs pruning from weeds (imitators). Same à --- For in the account which Hafen Slawkenbergius gives the world of his motives and occasions for writing, and spending so many years of his life upon this one work -- towards the end of his prolegomena, which by the bye should have come first, ---- but the bookbinder has most injudiciously placed it betwixt the analitical contents of the book, and the book itself

This reference to the bookbinder’s mistake in placing a section of the book in the wrong place foreshadows to the blank page in Volume VI where Shandy will be careful to remove the blame from his bookbinder. Perhaps these two references, read together, can say something to Sterne’s great investment in the production of his books (see Moss, Curtis, Yoklavich, et. al for all the interventions Sterne has made in the publishing and typesetting).

III.xxxviii à And to do justice to Slawkenbergius, he has entered the list with a stronger lance, and taken a much larger career in it, than any one man who had ever entered it before him, ---- and indeed, in many respects, deserves to be en-nich'd as a prototype for all writers, of voluminous works at least, to model their books by, ---- for he has taken in, Sir, the whole subject, -- examined every part of it, dialectically, -- then brought it into full day ; dilucidating it with all the light which either the collision of his own natural parts could strike, --- or the profoundest knowledge of the sciences had impowered him to cast upon it, ---- collating, collecting and compiling, -- begging, borrowing, and stealing, as he went along, all that had been wrote or wrangled thereupon in the schools and porticos of the learned : so that Slawkenbergius his book may properly be considered, not only as a model, -- but as a thorough-stitch'd DIGEST and regular institute of noses ; comprehending in it, all that is, or can be needful to be known about them.

This seems to also connect to Shandy’s description of the impossible project of the Tristrapedia, and makes the reader question the realistic possibility of “collating, collecting and compiling, -- begging, borrowing, and stealing” everything that could be said about a given topic. IV.pre à I dip not my pen into my ink to excuse the surrender of yourselves -- 'tis to write your panegyrick. Shew me a city so macerated with expectation -- who neither eat, or drank, or slept, or prayed, or hearkened to the calls either of religion or nature for seven and twenty days together, who could have held out one day longer.

IV.vii à So stood my father, holding fast his fore-finger betwixt his finger and his thumb, and reasoning with my uncle Toby as he sat in his old fringed chair, valanced around with party-coloured worsted bobs -- O Garrick ! what a rich scene of this would thy exquisite powers make ! and how gladly would I write such another to avail myself of thy immortality, and secure my own behind it.

IV.ix à - What a lucky chapter of chances has this turned out ! for it has saved me the trouble of writing one express, and in truth I have anew already upon my hands without it ---- Have not I promised the world a chapter of knots ? two chapters upon the right and the wrong end of a woman ? a chapter upon whiskers ? a chapter upon wishes ? -- a chapter of noses ? -- No, I have done that -- a chapter upon my uncle Toby's modesty ? to say nothing of a chapter upon chapters, which I will finish before I sleep -- by my great grandfather's whiskers, I shall never get half of 'em through this year.

Shandy enumerates all the different subjects he has promised to write about, once again playing with the dangerous (or exciting) looming of infinite possibilities.

IV.x à Now this, you must know, being my chapter upon chapters, which I promised to write before I went to sleep, I thought it meet to ease my conscience entirely before I lay'd down, by telling the world all I knew about the matter at once : Is not this ten times better than to set out dogmatically with a sententious parade of wisdom, and telling the world a story of a roasted horse -- that chapters relieve the mind -- that they assist -- or impose upon the imagination -- and that in a work of this dramatic cast they are as necessary as the shifting of scenes -- with fifty other cold conceits, enough to extinguish the fire which roasted him. -- O ! but to understand this, which is a puff at the fire of Diana's temple-- you must read Lon-ginus -- read away -- if you are not a jot the wiser by reading him the first time over -- never fear -- read him again -- Avicenna and Licetus, read Aristotle's metaphysicks forty times through a piece, and never understood a single word. -- But mark the consequence -- Avicenna turned out a desperate writer at all kinds of writing -- for he wrote books de omni scribili ; and for Licetus (Fortunio) though all the world knows he was born a foetus *, of no more than five inches and a half in length, yet he grew to that astonishing height in literature, as to write a book with a title as long as himself ---- the learned know I mean his Gonopsychan-thropologia, upon the origin of the human soul. The chapter on chapters ends up being another pondering on the nature of time and length, and it explains the necessity of breaks and pauses in a text. However, chapters do not necessarily (as they certainly don’t here!) imply beginnings or ends—much like reading a book from cover to cover does not imply the book won’t be read again, and that select chapters won’t be excerpted for more careful reading.

IV.xiii à Was every day of my life to be as busy a day as this, -- and to take up, -- truce -- I will not finish that sentence till I have made an observation upon the strange state of affairs between the reader and myself, just as things stand at present -- an observation never applicable before to any one biographical writer since the creation of the world, but to myself -- and I believe will never hold good to any other, until its final destruction ---- and therefore, for the very novelty of it alone, it must be worth your worships attending to. I am this month one whole year older than I was this time twelve-month ; and having got, as you perceive, almost into the middle of my fourth volume -- and no farther than to my first day's life -- 'tis demonstrative that I have three hundred and sixty-four days more life to write just now, than when I first set out ; so that instead of advancing, as a common writer, in my work with what Ihave been doing at it -- on the contrary, I am just thrown so many volumes back -- was every day of my life to be as busy a day as this -- And why not ? -- and the transactions and opinions of it to take up as much description -- And for what reason should they be cut short ? as at this rate I should just live 364 times faster than I should write -- It must follow, an' please your worships, that the more I write, the more I shall have to write -- and consequently, the more your worships read, the more your worships will have to read. We get yet another reference to time, and the impossibility of making one’s writing mimic the literal passing of time. Though we are four volumes in, Tristram is only just been born, and at this rate the narrative will never end. Same è As for the proposal of twelve volumes a year, or a volume a month, it no way alters my prospect -- write as I will, and rush as I may into the middle of things, as Horace advises, -- I shall never overtake myself -- whipp'd and driven to the last pinch, at the worst I shall have one day the start of my pen -- and one day is enough for two volumes – and two volumes will be enough for one year. –

IV.xv àI Wish I could write a chapter upon sleep. A fitter occasion could never have presented itself, than what this moment offers, when all the curtains of the family are drawn -- the candles put out -- and no creature's eyes are open but a single one, for the other has been shut these twenty years, of my mother's nurse. It is a fine subject! And yet, as fine as it is, I would undertake to write a dozen chapters upon button-holes, both quicker and with more fame than a single chapter upon this.

IV.xvii à The different weight, dear Sir, -- nay even the different package of two vexations of the same weight, -- makes a very wide difference in our manners of bearing and getting through with them. -- It is not half an hour ago, when (in the great hurry and precipitation of a poor devil's writing for daily bread) I threw a fair sheet, which I had just finished, and carefully wrote out, slap into the fire, instead of the foul one.

IV.xxv. à But the painting of this journey, upon reviewing it, appears to be so much above the stile and manner of any thing else I have been able to paint in this book, that it could not have remained in it, without depreciating every other scene ; and destroying at the same time that necessary equipoise and balance, (whether of good or bad) betwixt chapter and chapter, from whence the just proportions and harmony of the whole work results. For my own part, I am but just set up in the business, so know little about it -- but, in my opinion, to write a book is for all the world like humming a song -- be but in tune with yourself, madam, 'tis no matter how high or how low you take it. – Shandy makes another reference to chapters that, for being too good, risk overshadowing the entire work and must thus be edited out. IV.xxvi à As Yorick pronounced the word point blank, my uncle Toby rose up to say something upon projectiles ---- when a single word, and no more, uttered from the opposite side of the table, drew every one's ears towards it -- a word of all others in the dictionary the last in that place to be expected -- a word I am ashamed to write -- yet must be written -- must be read ; -- illegal -- uncanonical -- guess ten thousand guesses, multiplied into themselves -- rack -- torture your invention for ever, you're where you was -- In short, I'll tell it in the next chapter.

One of Sterne’s many playful exchanges with the reader, in which we are teased with the promise of the worst of words and are only later reminded that our imagination is always a better substitution to a literal description on the page.

V.xvi à In about three years, or something more, my father had got advanced almost into the middle of his work. – Like all other writers, he met with disappointments. -- He imagined he should be able to bring whatever he had to say,into so small a compass, that when it was finished and bound, it might be rolled up in my mother's hussive. -- Matter grows under our hands. -- Let no man say, -- “Come -- I'll write a duodecimo.” Shandy refers to his father’s inability to complete his Tristrapedia and immediately reminds the reader of the meanderings of his own narrative. The fact that “matter grows under our hands” will be a recurring theme in the book. V.xx à My uncle Toby had just then been giving Yorick an account of the Battle of Steenkirk, and of the strange conduct of count Solmes in ordering the foot to halt, and the horse to march where it could not act; which was directly contrary to the king's commands, and proved the loss of the day. There are incidents in some families so pat to the purpose of what is going to follow, -- they are scarce exceeded by the invention of a dramatic writer ; -- I mean of ancient days. ----

The time for reverencing the Classics was over—in the 18th century, “novel” was the buzz word—writers wanted innovation, originality and the mark of true genius. This, according to Warner, was a response to the growing print culture and the necessity to respond to “the press’ thirst for new material” (134).

V.xxvi à First, Had the matter been taken into consideration, before the event happened, my father certainly would have nailed up the sash-window for good an' all ; --which, considering with what difficulty he composed books, -- he might have done with ten times less trouble, than he could have wrote the chapter : this argument I foresee holds good against his writing the chapter, even after the event; but 'tis obviated under the second reason, which I have the honour to offer to the world in support of my opinion, that my father did not write the chapter upon sash-windows and chamber-pots, at the time supposed, -- and it is this. ---- That, in order to render the Tristrapædia complete, -- I wrote the chapter myself.

The narrative of the sash-window incident intertwines all the different stories being told: it interpolates the actual book’s telling of it with Walter’s proposed (fiction) chapter on the Tristrapedia, which Tristram’s decision to write the chapter himself, both as part of his opinions and as a last addition to his father’s work. VI.xvii àIn all nice and ticklish discussions, -- (of which, heaven knows, there are but too many in my book) -- where I find I cannot take a step without the danger of having either their worships or their reverences upon my back -- I write one half full, -- and t'other fasting ; -- or write it all full, -- and correct it fasting; -- or write it fasting, -- and correct it full, for they all come to the same thing : -- So that with a less variation from my father's plan, than my father's from the Gothick -- I feel myself upon a par with him in his first bed of justice, -- and no way inferior to him in his second. -- These different and almost irreconcileable effects, flow uniformly from the wise and wonderful mechanism of nature, -- of which, -- be her's the honour. -- All that we can do, is to turn and work the machine to the improvement and better manufactury of the arts and sciences. Now, when I write full, -- I write as if I was never to write fasting again as long as I live ; -- that is, I write free from the cares, as well as the terrors of the world. -- I count not the number of my scars, -- nor does my fancy go forth into dark entries and bye corners to antedate my stabs. -- In a word, my pen takes its course ; and I write on as much from the fullness of my heart, as my stomach. -- But when, an' please your honours, I indite fasting, 'tis a different history. -- I pay the world all possible attention and respect, -- and have as great a share (whilst it lasts) of that understrapping virtue of discretion, as the best of you. -- So that betwixt both, I write a careless kind of a civil, nonsensical, good humoured Shandean book, which will do all your hearts good -- -- And all your heads too, -- provided you understand it.

Shandy himself decides upon a definition of “Shandean” style.

VI.xxi à -- for my uncle Toby took the liberty of incroaching upon his kitchen garden, for the sake of enlarging his works on the bowling green, and for that reason generally ran his first and second parallels betwixt two rows of his cabbages and his collyflowers ; the conveniences and inconveniences of which will be considered at large in the history of my uncle Toby's and the corporal's campaigns, of which, this I'm now writing is but a sketch, and will be finished, if I conjecture right, in three pages (but there is no guessing) -- The campaigns themselves will take up as many books ; and therefore I apprehend it would be hanging too great a weight of one kind of matter in so flimsy a performance as this, to rhapsodize them, as I once intended, into the body of the work -- surely they had better be printed apart, -- we'll consider the affair -- so take the following sketch of them in the mean time.

This is one of many passages in which Tristram reminds us that he is writing extemporaneously, and that we are, as readers, not only privy of the finished, printed work, but somehow also privy to the planning and process of preparing the book for the press. Time is compressed, and we are left expectant of a finished volume that is already finished.

VI. xxxvi àNOW, because I have once or twice said, in my inconsiderate way of talking, That I was confident the following memoirs of my uncle Toby's courtship of widow Wadman, whenever I got time to write them, would turn out one of the most compleat systems, both of the elementary and practical part of love and love-making, that ever was addressed to the world -- are you to imagine from thence, that I shall set out with a description of what love is?

Early writers like Haywood and Behn capitalized on the many ways to describe and understand love, and presented readers with a myriad of points-of-view with which to understand their characters’ motivations. VI.xl à Pray can you tell me, -- that is, without anger, before I write my chapter upon straight lines -- by what mistake -- who told them so -- or how it has come to pass, that your men of wit and genius have all along confounded this line, with the line of GRAVITATION.

VI.xl à (straight lines) If I mend at this rate, it is not impossible -- by the good leave of his grace of Benevento's devils -- but I may arrive hereafter at the excellency of going on even thus ;which is a line drawn as straight as I could draw it, by a writing-master's ruler, (borrowed for that purpose) turning neither to the right hand or to the left. This right line, -- the path-way for Christians to walk in ! say divines -- -- The emblem of moral rectitude ! says Cicero -- -- The best line ! say cabbage-planters -- is the shortest line, says Archimedes, which can be drawn from one given point to another. --

Linear narrative becomes a literal, physical line that can be drawn on paper with a ruler.

See image on Tristrapedia webpage, under “Stolen.”