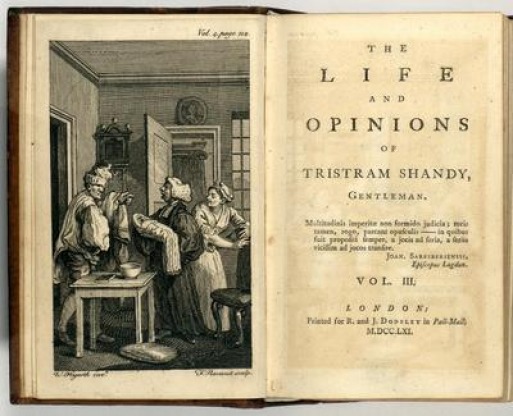

Quick and Easy Guide to Reading Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy

1) Start from the beginning. As with every novel, you must try to get an understanding of the plot, its central characters, and its central themes. If the narrator is the protagonist, you may, as a reader, attempt to uncover what his/her motives are with telling this piece. Since Tristram Shandy (from this point forward, TS) has a very hazy sense of plot, a complicated set-up of characters and their relative importance, and no better theme than the chaos of first-person consciousness, you will be ready to understand that this book cannot be approached by common linear methods of understanding.

2) Read Aristotle, Cervantes, Bacon, Locke, Swift, Montaigne, the history of the kings of England (and the battles of England), treatises on medicine, anatomy, law, religion and natural history, and so on and so forth, ad infinitum. Not only is the narrator interested in these authors, but these themes become important cultural, social and historical mockeries references to the events taking place in the novel. Further, in order to comprehend the central characters and their behaviors, the reader must have a firm understanding of their educational and philosophical backgrounds.

3) Unread Aristotle, Cervantes, Bacon, Locke, Swift, Montaigne, the history of the kings of England (and the battles of England), treatises on medicine, anatomy, law and natural history, and so on and so forth, ad infinitum. A careful reader will quickly realize (with a hearty laugh) that these references are meant to confound, criticize, demonstrate, counterbalance and destabilize the reading of the book. The narrator (as a good reader will have noticed, naturally) makes a mockery of the learned wit ideal, and wittily demonstrates how little learning one can get from trying to learn a bit of everything (cf. Tristram’s failed revolutionary birthing).

4) Flip through the book and read the ending, in a desperate keen attempt to grasp a sense of plot. Something about a Cock and a Bull? It is not supposed to make sense, you see, and yet it is so illuminating. The protagonist, having finally been born, reminisces back to a not-too-long ago past of his adult travels only to return back to the promised end. There is no sense of time, progression or even climax. But then again, the narrator had already warned you, on several occasions, that this was not going to be a straight up account of anything in particular—e.g.: “The story went on—and on—it had episodes in it—it came back, and went on—and on again; there was no end of it—the reader found it very long— ” (431). But don’t be frustrated; you’re a faithful reader who can enjoy digressions as well as the next gal.

5) Give up on the plot and attempt a post-modern analysis of the use of visuals elements. The black pages, following Yorick’s death (it’s existential; it’s disturbing; it’s…a moment of silence!); the empty spaces in volume III (reproduce the “original” excommunication, disrupt the curse, force pause); the illustrations in p. 165-6 (I am sure the reader has figured that one out already?); foreign language interventions; dashes and long lines, asterisks, lines and scribbles (333), and blank pages throughout. These elements contribute to the great disruption and mockery of the arduous process of reading and writing.

6) Take a break and watch Seinfeld. This is an important step to remind yourself that plotless, de-centralized stories can be not only entertaining but easy to follow. It may give you, as a reader, the power to understand TS as a series of seemingly disconnected slices of life strung together with the addition of somewhat central characters, punctuated with the eventual important, memorable event, like the birth of the protagonist (Seinfeld) and the lost car in the parking lot (Shandy). Wait, reverse those last two examples.

7) Make a list of characters and events to guide your reading. Some basics must include: Walter Shandy and Uncle Toby, Dr. Slop, Corporal Trim, Obadiah, Yorick, chambermaid Susannah, the midwife, Widow Wadman and…oh, Mrs. Shandy. Avoid realizing that most of the women in this story have some kind of sexual role. Save the analytical perspectives for later.

8) Realize that this novel may actually be more interested in peripheral deliberations, so make a list of those, too. Some places to get started may include: the nature of the female anatomy, the nature of Wit, the nature of noses, the nature of names, the evil chestnut, the impossible search for linearity and teleology, not to mention all the promised and never delivered chapters.

9) Watch the movie Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story. The ill fated attempt to adapt this novel into a movie automatically fails when the director decides to focus on the life of the title character and ultimately realizes that said character is barely relevant to the end of the story. The result is a discombobulated mockumentary in which the actors try to come to terms with their own feelings about the story. There is a moral to all of their struggles, however (you’ll have to watch the movie).

10) Give up altogether, and realize that this text enables multiple readings, almost like a choose your own adventure book. This is where this site comes in! I will get you started with the ways to read this book with an eye to print culture, writing and production. But this is only one of many adventures you can find.

2) Read Aristotle, Cervantes, Bacon, Locke, Swift, Montaigne, the history of the kings of England (and the battles of England), treatises on medicine, anatomy, law, religion and natural history, and so on and so forth, ad infinitum. Not only is the narrator interested in these authors, but these themes become important cultural, social and historical mockeries references to the events taking place in the novel. Further, in order to comprehend the central characters and their behaviors, the reader must have a firm understanding of their educational and philosophical backgrounds.

3) Unread Aristotle, Cervantes, Bacon, Locke, Swift, Montaigne, the history of the kings of England (and the battles of England), treatises on medicine, anatomy, law and natural history, and so on and so forth, ad infinitum. A careful reader will quickly realize (with a hearty laugh) that these references are meant to confound, criticize, demonstrate, counterbalance and destabilize the reading of the book. The narrator (as a good reader will have noticed, naturally) makes a mockery of the learned wit ideal, and wittily demonstrates how little learning one can get from trying to learn a bit of everything (cf. Tristram’s failed revolutionary birthing).

4) Flip through the book and read the ending, in a desperate keen attempt to grasp a sense of plot. Something about a Cock and a Bull? It is not supposed to make sense, you see, and yet it is so illuminating. The protagonist, having finally been born, reminisces back to a not-too-long ago past of his adult travels only to return back to the promised end. There is no sense of time, progression or even climax. But then again, the narrator had already warned you, on several occasions, that this was not going to be a straight up account of anything in particular—e.g.: “The story went on—and on—it had episodes in it—it came back, and went on—and on again; there was no end of it—the reader found it very long— ” (431). But don’t be frustrated; you’re a faithful reader who can enjoy digressions as well as the next gal.

5) Give up on the plot and attempt a post-modern analysis of the use of visuals elements. The black pages, following Yorick’s death (it’s existential; it’s disturbing; it’s…a moment of silence!); the empty spaces in volume III (reproduce the “original” excommunication, disrupt the curse, force pause); the illustrations in p. 165-6 (I am sure the reader has figured that one out already?); foreign language interventions; dashes and long lines, asterisks, lines and scribbles (333), and blank pages throughout. These elements contribute to the great disruption and mockery of the arduous process of reading and writing.

6) Take a break and watch Seinfeld. This is an important step to remind yourself that plotless, de-centralized stories can be not only entertaining but easy to follow. It may give you, as a reader, the power to understand TS as a series of seemingly disconnected slices of life strung together with the addition of somewhat central characters, punctuated with the eventual important, memorable event, like the birth of the protagonist (Seinfeld) and the lost car in the parking lot (Shandy). Wait, reverse those last two examples.

7) Make a list of characters and events to guide your reading. Some basics must include: Walter Shandy and Uncle Toby, Dr. Slop, Corporal Trim, Obadiah, Yorick, chambermaid Susannah, the midwife, Widow Wadman and…oh, Mrs. Shandy. Avoid realizing that most of the women in this story have some kind of sexual role. Save the analytical perspectives for later.

8) Realize that this novel may actually be more interested in peripheral deliberations, so make a list of those, too. Some places to get started may include: the nature of the female anatomy, the nature of Wit, the nature of noses, the nature of names, the evil chestnut, the impossible search for linearity and teleology, not to mention all the promised and never delivered chapters.

9) Watch the movie Tristram Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story. The ill fated attempt to adapt this novel into a movie automatically fails when the director decides to focus on the life of the title character and ultimately realizes that said character is barely relevant to the end of the story. The result is a discombobulated mockumentary in which the actors try to come to terms with their own feelings about the story. There is a moral to all of their struggles, however (you’ll have to watch the movie).

10) Give up altogether, and realize that this text enables multiple readings, almost like a choose your own adventure book. This is where this site comes in! I will get you started with the ways to read this book with an eye to print culture, writing and production. But this is only one of many adventures you can find.